All hikes to Machu Picchu involve going to ‘high altitude‘, and therefore come with obvious altitude sickness risks.

It is important that you understand these risks so that you can take the best preventative actions, as well as be well-informed on how to deal with altitude sickness symptoms, and it’s severe variants – High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) and High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) – both are very rare conditions on Machu Picchu treks.

In this detailed article on Machu Picchu altitude sickness I have provided general information on the process of acclimatisation, an overview on altitude sickness, HACE and HAPE, as well as provided details on preventative medications like Diamox and natural remedies like coca tea.

At the end of the article I have provided useful information on travel and trekking insurance, which I recommend you have for your Machu Picchu trek.

A variety of authoritative resources have been used to put this article together. Rick Curtis’ Outdoor Action Guide to High Altitude, written for Princeton University, and insight from Altitude.org were two particularly helpful resources.

Disclaimer: The information on this page is provided as an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. The information is not intended to be patient education, does not create any patient-physician relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment. Research in this area is always progressing which may mean some of this information is out of date. It is your responsibility to seek the latest information should you be going to high altitude.

Altitude Sickness - A Guide

Acclimatisation

Acclimatisation refers to the process by which the body becomes accustomed to lower levels of oxygen, and is only achieved by spending time at various levels of altitude before progressing higher.

In mountaineering parlance, there are three main levels of altitude:

- High altitude describes the altitude zone between 2,500m and 3,500m

- Very high altitude is between 3,500m and 5,500m

- Extreme altitude is above 5,500m.

There are other zones above extreme altitude, but these are limited to the Himalayas – like the death zone which is above 8,000m!

Most people can ascend from sea level to 2,400m without experiencing altitude sickness symptoms, but beyond this height changes in oxygen and pressure levels start having an impact on people’s physiology.

Cusco Altitude

What makes treks to Machu Picchu tough, and potentially dangerous, is the speed at which you arrive at high altitude. Most, if not all visitors to Machu Picchu, arrive by flying into Cusco which sits at 3,400m – on the boundary of the high and very high altitude zone.

At sea level (i.e. Lima, Peru) oxygen saturation in the air is about 21% and barometric pressure is around 760mmHg (millimetres of mercury).

As one ascends oxygen saturation stays relatively constant but air density drops, which means the % of oxygen per breath reduces (imagine oxygen molecules moving further and further away from each other at higher altitudes).

For examples, at 3,600m (just above Cusco), barometric pressure is around 480mmHg, and oxygen per breath is 40% less that at sea level!

Acclimatisation Begins in Cusco

A few hours after arriving in Cusco you will undoubtedly feel the ‘thinness’ in the air, and even walking short distances will put you out of breath.

The good news is that the body is very ingenious and immediately deploys four measures to start dealing with the lower levels of oxygen per breath.

- First, you will notice that your breathing becomes faster and deeper (even at rest) – this is a good sign so embrace it!

- The second thing that happens is that the number of red blood cells – which carry oxygen in your blood – increases.

- Third, an increase in pressure in your pulmonary capillaries forces blood into areas of the lungs that are not used when breathing at sea level.

- And finally, a certain enzyme is secreted which promotes more effective transfer of oxygen from your haemoglobin to your blood tissue.

Given enough time at a ‘reasonable’ starting altitude, the body will acclimatise, and progressing to higher altitudes, whilst remaining asymptomatic, becomes possible.

To illustrate this point, mountaineers have come up with a term called the acclimatisation line, which describes an altitude line at which someone’s altitude sickness symptoms appear.

Let’s say that your altitude line is just over 3,000m. On day one you trek to 3,000 meters and remain asymptomatic as you are below your acclimatisation line.

A night or two at this altitude will ensure that you are fully acclimatised and your line might increase to 3,800m. You then trek to 3,700m and remain asymptomatic, but if you continued further to 4,000m you might start experiencing altitude sickness.

Descent back down to below your acclimatisation line (3,800m) to rest for a day or two should resolve any altitude sickness symptoms. Continued ascent though, would only worsen your condition.

The point: Rest for a day or two near one’s acclimatisation line usually resolves altitude sickness symptoms, but continued ascent before proper acclimatisation will almost guarantee that your symptoms will worsen and further acclimatisation will not occur. Getting below the altitude line where symptoms begun is critical for one’s safety.

Acclimatising On Machu Picchu Treks

How does acclimatisation apply to treks to Machu Picchu?

As I mentioned above, Cusco is already at high altitude and generally above most people’s acclimatisation line.

Hence symptoms of mild altitude sickness (see below for details) are common.

For trekkers, the best solution in our opinion, is to stay in Cusco or the Sacred Valley for at least two days to starve off mild altitude sickness symptoms and acclimatise (most tour operators include a two day acclimatisation period in Cusco as part of their tour package).

All routes to Machu Picchu involve going over high passes (over 4,500m), so acclimatising early, albeit at a relatively high altitude, is worthwhile.

Alternatively, if you are just visiting Machu Picchu (2,430m) by train, it is possible to fly into Cusco (3,400m) and then descend immediately into the Sacred Valley (1 hour bus/car ride) to the towns of Urabamaba (2,800m) or Ollantaytambo (2,792m) where it is easier to start the acclimatisation process.

Resting here for a day or two before proceeding to Machu Picchu by train, which departs from Ollantaytambo, can help lower the probability of experiencing altitude sickness.

That being said you will still need to return to Cusco after Machu Picchu which could result in the onset of altitude sickness symptoms.

The absolute ideal scenario would be to fly into Cusco and then immediately drive to the Sacred Valley to rest for a couple of days. Then return to Cusco to rest for a few days, and then begin your trek. Most people don’t have the time or inclination to do this.

Get a Machu Picchu trek quote

Start planning your Machu Picchu hiking holiday.

Altitude Sickness Symptoms

Altitude sickness, also known as Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) or altitude illness, is a pathological condition caused by going to high altitudes, too fast.

Most people start experiencing altitude sickness at 3,000m, some can experience altitude sickness symptoms as low as 2,400m. Unfortunately there is no correlation between age, fitness, health and gender that can help predict one’s susceptibility to altitude sickness.

All we know for sure is that ascending more than 500m a day from 2,400m increases the probability of altitude sickness, as does exercising at high altitude and dehydration.

Altitude sickness symptoms can be separated into three levels – mild, moderate and severe. One typically moves from mild symptoms to more acute and extreme symptoms as the condition worsens.

In other words, there are usually early warning signs that you are suffering from altitude sickness and that it is worsening. Severe conditions, like HACE and HAPE, can occur as symptoms deteriorate.

Mild Altitude Sickness

Mild altitude sickness symptoms include: fatigue, headaches, nausea and lost appetite, dizziness, disturbed sleep and shortness of breath.

Mild altitude sickness symptoms typically present between 12-24 hours after arriving at altitude and are common for visitors to Cusco. Remaining for 24-48 hours at the altitude at which mild altitude sickness occurs usually resolves symptoms. Once symptoms have passed at the altitude they started, you can assume you have acclimatised to that altitude.

Moderate Altitude Sickness

Signs that you are suffering moderate altitude sickness include very bad headaches that aren’t relieved with medication (think the worst migraine you have ever had), awful nausea, sometimes resulting in vomiting, extreme fatigue and weakness, shortness of breath, and a feeling of decreased coordination (known as ataxia).

Most people suffering from moderate altitude sickness symptoms can still walk but ascent under these conditions will almost certainly result in worsening of the condition. Descent is the only cure for this condition and time should not be wasted in getting someone down to the altitude at which the symptoms were not present. Once the symptoms have subsided it is possible to continue ascending.

Severe Altitude Sickness

Severe altitude sickness symptoms include an inability to walk, extreme shortness of breath, loss of cognitive capacities (ability to think straight), hallucinations and fluid build on the lungs. HACE and HAPE are commonly associated with severe altitude sickness and occur when fluid leaks into the brain or through the capillary walls into the lungs, respectively. Ascent under these conditions is extremely dangerous and potentially fatal. Immediate decent is required.

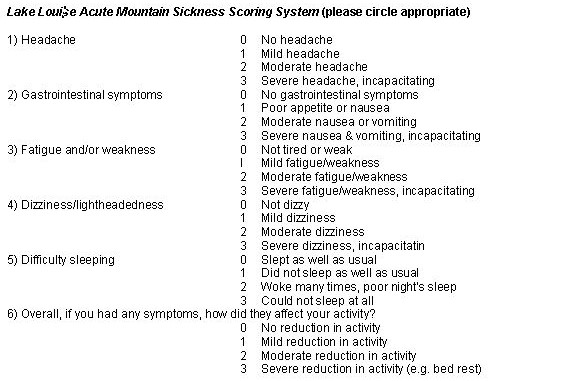

Lake Louise AMS Scorecard

The Lake Louise AMS system is one way that you can test how bad your altitude symptoms are. A score between 3-6 is a sign of mild to moderate altitude sickness, scores above 6 are a sign of severe altitude sickness.

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is a condition associated with severe altitude sickness, and occurs when pressure build-up results in fluid breaching the capillary walls in the cranium. It is a very rare condition on Machu Picchu treks.

HACE symptoms include very bad migraines, hallucination, loss of coordination and disorientation, memory loss, and ultimately loss of consciousness and coma.

HACE tends to strike at night. Time should not be wasted in getting someone down to lower altitudes if they have suspected HACE. Do not wait for daylight. Descend immediately.

If you have oxygen it can be administered along with a steroid called, dexamethasone, but these should only be used in conjunction with rapid descent.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

Like HACE, High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), is another fatal altitude sickness condition and involves fluid breaching the pulmonary capillaries and entering the lungs. Fluid in the lungs prevents effective exchange of oxygen to the bloodstream.

Signs that someone is suffering from HAPE include extreme shortness of breath (even at rest), very tight chest, the feeling of suffocating, particularly during sleep, coughing up white frothy fluid, hallucinations, extreme fatigue, and irrational behaviour.

Descent is paramount, but care should be taken not to exert the individual suffering from HAPE symptoms as this can worsen the condition. Any available oxygen should be administered. The drug, Nifedipine, has been shown to ameliorate the condition, but descent is the only cure.

Get a Machu Picchu trek quote

Start planning your Machu Picchu hiking holiday.

Golden Altitude Sickness Rules

A lot of the information above is doom and gloom. It is important to remember that severe altitude sickness and its variants. HACE and HAPE, are very rare on Mach Picchu treks.

You will not be trekking to extreme altitude and all routes have good altitude profiles that allow for adequate descents after going over high passes.

There are however, a number of golden rules to remember:

- If you feel unwell at altitude, assume it is altitude sickness.

- If you have symptoms of altitude sickness do not ascend further. In some cases this can mean going a little higher to go lower (i.e. going over a pass). Get over the pass quickly and descend.

- If symptoms get worse after waiting at a lower altitude, descend immediately.

In addition to these rules, I recommend following these basic principles:

- Acclimatise for a minimum of 2 days in Cusco – where you relax and drink lots of fluids.

- Ensure you remain well-hydrated on the trail – drink 2-3 litres of water a day.

- Go slowly, enjoy the scenery and don’t over-exert yourself.

- Avoid smoking, alcohol and stimulants on the trail.

- Work with a reputable operator who employ guides who understand the risks of altitude sickness and have adequate training / equipment to deal with any issues – I provide a free recommendation service here.

- Ascend in small increments of 500-700 meters a day, and try incorporate trek high, sleep low days. This last point is out of your control as the routes to Machu Picchu are already designed with these features embedded.

- Take a preventative medication like Acetazolamide (Diamox) as an extra precaution – more on this below.

Looking for a day tour? Here are my 5 favourite day tours around Cusco:

- Rainbow Mountain day trip (with meals)

- Moray and Salt Mines Quad Bike Tour

- Sacred Valley day tour

- Humantay Lake day tour

- Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu entrance tickets

See more Cusco day trips.

Medications & Natural Remedies

Diamox

Acetazolamide, known by the brand name Diamox, is a drug that has been proved effective in mitigating the effects of altitude sickness. It is a prophylactic (preventative medication), not a cure.

In other words it promotes faster acclimatisation and helps prevent the onset of altitude sickness, but does not cure it.

In some countries the drug requires a prescription, but in general it can be bought over the counter. One should however consult their doctor before using it. Pregnant women or people with kidney and liver issues should not take the drug.

The side effects include increased urination; numbness and tingling in fingertips, toes and nose; taste alterations; and nausea, vomiting and drowsiness.

The last three side effects can be confused with altitude sickness so it is recommended that one takes a short dose of Diamox a few weeks before departing for Machu Picchu to test any side effects.

Diamox is generally sold in 250g tablet format. Trekkers typically take 125g in the morning and the remaining 125g in the evening, starting one day before arriving in Cusco and finishing on the day one leave’s Cusco.

I believe it is worthwhile taking Diamox as a preventative measure but recommend consulting your doctor before you do so.

Coca Tea or Coca Leaves

Coca leaf plantation as seen on the Inca Jungle trek

Coca is a plant that grows naturally in Peru and features prominently in Andean culture for it’s medicinal and superstitious qualities.

A pharmacologically active ingredient in the coca plant, called the coca alkaloid accounts for about 0.8% of the fresh leaf and in its refined form makes cocaine. Drinking coca tea or chewing the leaves do not however produce the same effects as cocaine.

When chewed, coca can act as a mild stimulant and has been shown to repress hunger, fatigue, thirst and pain. Traditionally, various Andean cultures use the coca leaf for a number of medicinal, nutritional and religious purposes.

One traditional use is in the prevention of altitude sickness. Locals either chew the leaves or drink coca tea, and encourage tourists to do the same as a preventative measure.

There is however no conclusive evidence that coca leaves help prevent the onset of altitude sickness, or indeed help treat the symptoms.

The jury is also out on other natural medications like Ginkgo Biloba, although a research study in 2007 found evidence that G.Biloba does help prevent altitude sickness.

From our perspective, more research is required in these areas to draw conclusive remarks. That being said, if you are offered coca tea I wouldn’t turn it done.

Very good info to know before

Thanks Sim!